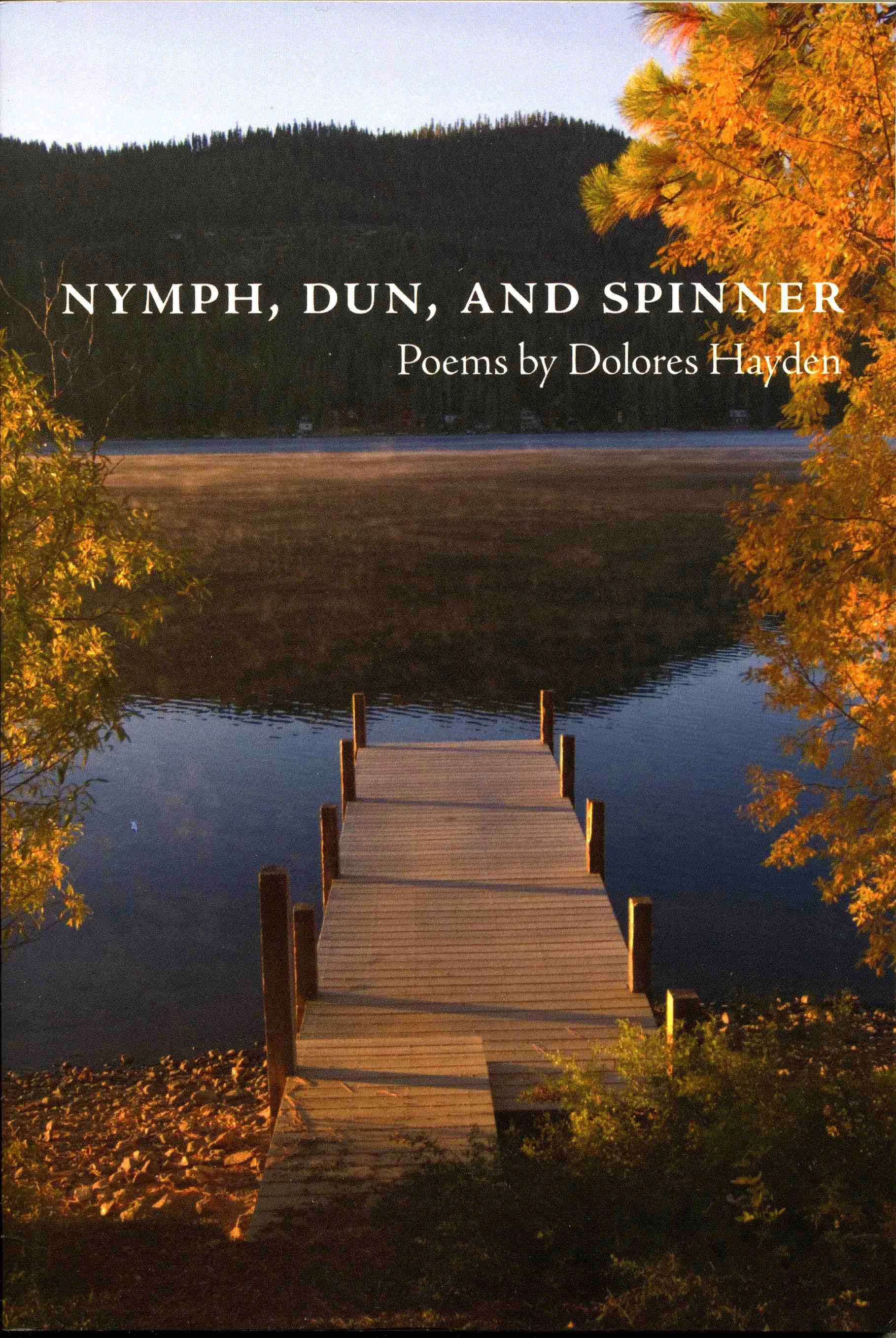

Nymph, Dun, and Spinner: Poems

At the edge of the Housatonic River, a fishing guide muses on “birth, midlife, and passing—the agile nymph, the olive dun, and the drowning red spinner.” This collection of poems book builds to a narrative sequence, and concludes with two elegies.

Praise for the book:

This is a pristine and radiant book of poems, each line sharp, clear, beautiful, and wise.

— Elizabeth Alexander

Dolores Hayden's precise gaze and chiselled language authoritatively convey her broad and deep knowledge. Whether the subject is fly fishing, ideal communities in the nineteenth century, or how (once upon a time) to fold the New York Times, Nymph, Dun, and Spinner is infused with restrained but piercing emotion, especially in the beautiful poems that invest objects with elegiac eloquence.

— Rachel Hadas

Poems from the book:

Nymph, Dun, and Spinner

We drive to narrow shops in distant strip malls

searching mink underfluff and peacock herl,

deer hair, seal fur, and black bear hair.

We knot the nymph, dun, and spinner, wind

the small unsinkable bodies, jerk the threads

into the muddlers, add the hooks. It takes

years of experience to calculate

a hook, judge the length, consider the weight,

know how ephemeroptera touch down

on water, how trout thrash and lunge.

We celebrate artifice, we factor panic,

hunger is not the same as pride

for man, woman, or fish. It is all practice,

no theory, tying the knots tightly,

knowing they will hold. Father and daughter,

our river races between granite shores

where gaunt men once sharpened scissors

and knives, shivering in noisy factories.

The town runs on waders and canoes now,

on February Reds and March Browns,

rapids and whirlpools, stars leaning into dawn.

We murmur the names, Parachute Adams,

McMurray Ant, Barret’s Bane, Cahill.

We could be two monks chanting a litany

as we guide novices to water and hills,

mark the hours, demand miracles —

Goddard’s Last Hope, Dambuster.

The skill in the tying, the skill with the rod,

the need to endure, my father speaks —

and of course, I listen. It is not pleasant,

far from my down-filled comforter, my thighs

deep in the rush of the hard river. I respect

his thousand facts of angling, I mark

the lure of his stories — R. S. Austin

tied a female spinner of fine yellow wool

from ram’s testicles in 1900. After he died,

his daughter sold “Tup’s Indispensable”

for twenty years. Like her, I’m second generation.

From my father, I learned birth,

mid-life, and passing — the agile nymph,

the olive dun, the drowning red spinner.

When I place my feet in the freezing river,

I map the geography of patience.

When I hurl a winged impersonator concocted

of blue cock hackle and red seal fur into the dawn,

I tend the history of fiction, pass it on.

First published by the Yeats Society of New York and by Atlanta Review.

Grave Goods

— Tang dynasty camel, painted earthenware, 600-900 A.D.

Life flows in the easy stride and flaring tongue

of the long-necked crying camel whose twin humps

bear man, boy, monkey, dog, puppy, and pig.

The monkey nibbles a plum, the dog lies quiet,

the puppy watches the busy monkey chew,

snout down, the pig snores in the noonday heat

as the camel’s weary hooves step west — Changan,

Dunhuang, Lop Nor, Kashgar, Samarkand.

Behind the driver, the boy sits facing backwards,

riding past all the towns with all the souks

and all the tents he might have lived and died in.

The driver smiles under his wide mustache,

confident in the market for fresh almonds,

fine silk, and lap dogs. Clever foreigner

wearing a pointed cap, he knows the way,

he never tires, he is the perfect conductor,

in his hands the trip to places so remote

begins to seem almost manageable.

And so the mingqi sculptor soothed the grief

of the dead boy’s relatives, conjuring trade

to entertain and profit him. And as for you,

admiring the wondrous camel here with me,

I dread that swaying seat on the camel’s back,

I would hold you by our fireside, if I could.

First published in Southwest Review and in The Best American Poetry 2009.